This post is notably longer than usual, and for good reason. However, my upcoming post on Prince Caspian, should mark a return to my typically succinct style.

“When Adam’s flesh and Adam’s bone

Sits at Cair Paravel in throne,

The evil time will be over and done.”

LWW | C.S. Lewis | Chapter VIII

I will admit—to my great embarrassment—that it took me twenty years to fall in love with The Lion the Witch and The Wardrobe. How is this possible for someone who proclaims their own Narnian-Super-Fandom so boldly? I assure you, I was as concerned as you are.

At age twelve, during my first attempt to read Narnia, I didn’t know much. All I knew was that the first book was often cited as, “Narnia’s Jesus story.” In light of this, I figured, “I know the story of the cross, I think I understand the doctrine of the atonement, and I’ve just seen the movie… surely I can skip this one!” So for eight long years, I ignored it.

Fast forward, and at age twenty-three (the year I was reborn a true Narnian), I had the privilege of studying all seven books in a theology class on C.S. Lewis. During said class, while I fell in love with the other six books, I came to unapologetically rank The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, as the worst. Not “last amongst equals”, no—I formally declared it my least favorite by a significant margin. I didn’t think it was outright bad, but it lacked—for me—the literary and spiritual flair of the others.

Each of the other six books had astounded me. Minimally, once per tale, I found myself in awe of Jesus as portrayed by Aslan, humbled in my brokenness as demonstrated by the sentient characters (humans and talking beasts alike), and astounded by the glories woven into the fabric of Narnia. Yet, for some reason, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, only mustered the feelings of “another old Sunday school lesson.”

Don’t get me wrong, Sunday School lessons are important, so I still found (spoiler alert) Edmund’s redemption and Aslan’s resurrection beautiful. But the other six books were more than beautiful. They displayed the glory of Christ, declared the depths of God’s love, and personalized abstract truths about the faith in ways that inspiring sermons, insightful classes, and illuminating commentaries never had.

I felt, in the other six books, as though C.S. Lewis had discipled me. But what was I to make of The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe? Was it possible Lewis hadn’t found his form for book one? Had he intentionally made the first installment simple? Or perhaps I, like Edmund Pevensie, was callous to the name of Aslan. Although, I’ve always viewed myself as more of a Lucy the Valiant…

Jokes aside, a humble eight years later, I am delighted to announce that The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe has ascended to the same place in my heart as the other six books. I get it now. Here’s what I realized.

Firstly, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe wasn’t thin or lacking (of course it wasn’t), my theology was!

Secondly, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, is more Narnia’s enthronement story than Narnia’s atonement story!

After careful consideration, I suppose I do look more like Edmund the Just.

My Thin Theology

If you grew up in an evangelical Bible church, you’re probably familiar with the doctrine of Imago Dei. In case you aren’t, it’s Latin, and it’s the theological term for the “Image of God.”

This refers to the ontological and anthropological reality—established in scripture—that Adam, Eve, and therefore all of humanity, were and are, made in the image of God!

“Then God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.’

So God created man in his own image,

in the image of God he created him;

male and female he created them.”

Genesis 1:26 | ESV

Amazing right? Yes! But why?

Even though I grew up in a relatively great church, and was taught about the Imago Dei at a young age, for at least half of my life it only meant one thing: that God gave humanity a conscience. Therefore, we are special/better/different than animals.

I’m not blaming my church, but for some reason Imago Dei was just a strange form of an “apologetic tool.” Worthy of being kept on the workbench, but rarely reached for.

I can vaguely remember times in late middle school and/or early high school when a sermon expounded on this, or a youth pastor hinted at a deeper meaning. However, no one, to my recollection, ever sat me down and told me straight, that the doctrine of Imago Dei is one of the most remarkable, controversial, and important religious claims of all time!

Since this isn’t a theology substack, I will spare you a “deep dive”, and briefly attempt to illuminate one of the Imago Dei’s most profound, though underappreciated facets. Imago Dei describes our being, yes, but it also describes our role.

In essentially all ancient worldviews, the “image of god” referred exclusively to emperors, and kings. They claimed to be the literal image of a God, and from this claim, derived their authority to rule.

To be clear, an appropriate analogy would not be:

God—owner of the company

King—chief executive officer

Nor would,

God—Sherif

Queen—Deputy

Or even,

God—King

Prince—Humanity

To be a king or queen, made in the image of a god, meant that you were an actual manifestation of a god’s real presence and authority. Therefore, when the Bible says, “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” It is an unfathomably big deal. It was also, historically, a completely unprecedented claim.

To borrow an Independence Day phrase, the Bible declares men and women, the whole lot of ‘em, “have been endowed by their creator with” some level of his own authority and power. We can see this within the broader narrative of Genesis, and the Bible. In fact, within the very text of Genesis 1:26. Adam and Eve are given “dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.”

Friends, the Bible’s claim that humans are Imago Dei, isn’t merely a claim that we’re smarter or have more mental faculties than animals. It isn’t even that some humans can rule as God’s image bearers. No, it’s that all humans—Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve—were made to rule in God’s image!

And when I came to realize that this is the central claim of The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, I finally fell in love with it!

Enthronement Over Atonement

Within each, and connecting every Narnia book there are easter-eggs for readers to find. Some of them are theological, others are lingual or medieval, and some of them are internal references. In fact, there are even clever references to Lewis’s other works!

For a lingual example, did you know the name “Aslan” is Turkish for Lion? That’s right, Narnia is one big pun…

I kid, and while this seems cute on the surface, I would guess that Lewis is genuinely paying homage to the fact that “Christ” is often misunderstood by children as the last name of Jesus. So, in Narnia, for all of our sakes, any confusion about the messiah’s name, title, and nature, is cleverly avoided. While tempted to introduce you all to the rich history of name puns in the Bible… alas… we must press on!

Here’s a more robust inter-Narnian example (without spoiling anything)! In the series conclusion, The Last Battle, the antagonist is an ape. If one pays close enough attention, they would note that in The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, apes are on the witch’s side. Additionally, in one of the last lines of dialogue in The Horse and His Boy, the following dig at apes is found,

“[Lucy said], let him go free on strait promise of fair dealing in the future. It may be that he will keep his word."

Maybe Apes will grow honest, Sister," said Edmund.”

The Horse and His Boy | Chapter XV

In case you missed it, the implication of this line is that it would be foolish to let “him go free”, because apes will never grow honest…

If you want more evidence that Lewis was tipping his hand—one constant motif in all of Lewis’s writing is this:

That which pretends to be, or is very close to human (like an ape) but isn’t, tends to be the most dangerous. Mr. Beaver even warns the children to this end within the pages of The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe.

“[The White Witch is] bad all through, Mr. Beaver,” said Mrs. Beaver.

“True enough, Mrs. Beaver,” replied he, “there may be two views about humans (meaning no offense to the present company). But there’s no two views about things that look like humans and aren’t.”

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe | Chapter VIII

If you’re familiar enough with Lewis’s writings, these become almost over the top fourth wall breaks. Though I would venture to say they are not noted by most young readers.

All of this is to say, that in addition to the fun connections outlined above, each Narnia book’s narrative is buoyed by a primary motif (often biblical/theological). And for years, perhaps decades, or perhaps for all 75 years The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe has been in print, readers have believed its primary motif to be atonement/redemption. So much so, that if you were to casually poke, or even desperately dig around the internet in search of LWW content—trust me when I say—all you would find are articles to this end.

But this substacker begs to differ…

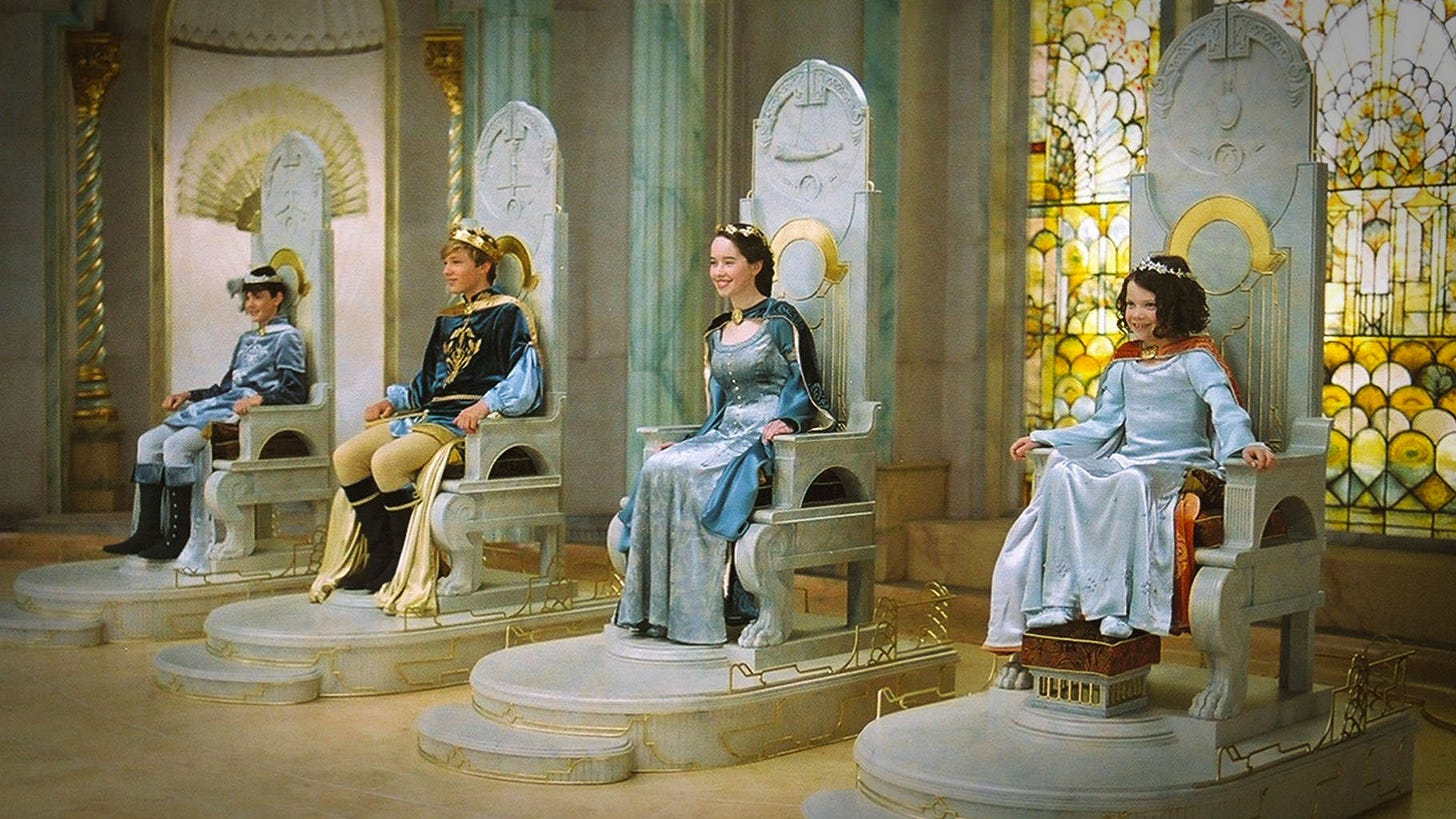

As I’ve already stated, Edmund’s redemption and Aslan’s sacrifice is glorious, but I have become convinced through repeated readings, that The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe was written primarily as the enthronement story of the Pevensie children; intended to teach its readers that all those made in the image of God (Imago Dei)—whether they’re brave older brothers (Peter), caring older sisters (Susan), imaginative little girls (Lucy), or “poisonous little beasts” (Edmund)—were made and redeemed to be kings and queens.

Now, I am going to argue my case, but please, if you haven’t read LWW, or want to discover this theme on your own— subscribe, click away, (re)read the book with this in mind, and then come back!

Spoilers ahead!

For efficiency’s sake, I am simply going to list the evidence. Let me know what your favorite point is, or if you disagree!

Before the children enter Narnia, the first conflict ever shown is an inter-sibling-power-struggle. On its own, this can be dismissed as normal children’s material, but I think the rest of the novel reveals Lewis is tapping into the classic tropes of royal sibling rivalries.

Note that Aslan later settles the debate, informing Peter he is to be “High King” over the rest.

Through Lucy and Mr. Tumnus, the first dramatically relevant plot point revealed is that Narnia is “under the thumb” (a phrase historically used almost exclusively in reference to national leaders) of an evil witch. By the way, this witch wants all Imago Dei children kidnapped. I wonder why?

When Edmund and the white witch meet, the White Witch calls herself the “Queen of Narnia.” This foreshadows at the primary tension of the book.

The White Witch offers Edmund kingship over his brother and sisters for his cooperation. This is key. The witch’s eventual claim to Edmund’s life is based on his treachery specifically. He—a would-be king of Narnia—plans to betray his royal siblings to the enemy.

When all four children arrive in Narnia, they put on the fur coats hanging in the wardrobe, and the narrator says,

The coats were rather too big for them so that they came down to their heels and looked more like royal robes than coats when they had put them on. (emphasis added)

This one is so good, and an obvious fourth wall break once you have eyes to see it. If not for this theme, surely they would have been described as ridiculous or silly. Classic Lewis!

If at this point you aren’t convinced, the conversation with Mr. and Mrs. Beaver thoroughly, and irrefutably, establishes that the Pevensie children have come to Narnia to fulfill the prophecy, and be enthroned at Cair Paravel. This is the point of the book. This is why the witch wants the children kidnapped.

When Adam’s flesh and Adam’s bone

Sits at Cair Paravel in throne,

The evil time will be over and done.The Beavers also reveal that Jadis (the witch’s name) stakes her false claim to the throne by pretending to be human! Do you see it yet? Because she isn’t a Daughter of Eve, she has no right to rule. It doesn’t matter how powerful she is, she is not Imago Dei!

When Edmund’s betrayal is complete, and he leaves his family for Jadis, he leaves his fur coat (royal robes) behind. Unbeknownst to him, in pursuit of a throne (and turkish delight) he’s forfeited the throne he already has for a witch’s dungeon, and certain death.

As the children run to Aslan, Father Christmas comes from a far away land to shower the “newborn king” and queens of Narnia with gifts… This might sound goofy at first, and though we’re told Father Christmas comes to Narnia because the witch’s spell is broken by Aslan, think about it… Christmas couldn’t come to Narnia until the long awaited kings and queens arrived.

When the three children meet Aslan, we are told two leopards carry his crown and standard. Nowhere else in the entire series is the kingliness of Aslan so formally emphasized. He never has a crown (other than his mane), let alone a standard again.

Edmund is forgiven and restored to his brothers and sisters prior to Aslan’s sacrifice. Again, the witch’s claim on Edmund’s life is specifically based upon his treachery—nothing else. I don’t want to make too much of this, as even Jesus forgave sins before going to the cross. But I think this ordering of events, makes Aslan’s sacrifice appear to be for Edmund’s kingship, and for the prophecy, just as much as, if not more than, his redemption. It would seem, though Narnia is not an allegory, Lewis is working with a fairly robust atonement theory. We shouldn’t be surprised.

The resolution of this tale is not the resurrection, the saving of the statues, the restoration of order, or even the death of the Jadis (she’s disposed of with comical quickness by Aslan). The resolution of the plot is the enthronement of the Pevensie children at Cair Paravel.

Aslan leaves Narnia once the children are established, entrusting his world to their care and stewardship.

The narrator takes the time to assure us that the Pevensies were in fact great rulers.

Fun fact: Cair Paravel means lesser/lower Court. Another language joke from Lewis, reminding his readers all kings and queens rule under the authority of Aslan!

Now, if I haven’t offended you too much, here’s why this is important. It all boils down to Imago Dei.

Humans, made in the image of God, were not made to be passive observers of the world around us. Even Adam and Eve in the garden, were called to name things, subdue things, cultivate things, etc. Likewise, Christians are not saved to be passive observers. The church is called to take up the royal mantle neglected by humanity in its sinful state. If you’re a believer, you were saved to participate in the work of the church, which is to participate in the establishment of the kingdom of God here on earth as it is in heaven.

Think of Moses, Joseph, the Judges of Israel, David, Daniel, Esther, all the prophets, Mary, all of the Apostles, etc. God uses people to accomplish his will. So does Aslan.

There are prominent shades of Christianity, that get people in the door of the church by telling them Jesus died for their sins, but then tell them nothing else! The result is often a bunch of Christians who know that,

“…by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast.” | Ephesians 2:8-9

Yet, neglect to remember, or never learn the next verse…

“…we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.” | Ephesians 2:10

And therefore don’t feel compelled to do much good for the kingdom, let alone the world.

The Chronicles of Narnia, and The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe (second perhaps only to The Silver Chair) oppose this mindset beautifully. Children are always called into Narnia to help Narnia!

The Pevensies set out to rescue Mr. Tumnus (and in the end succeed), go on a noble quest, fight wolves, win a huge battle, heal people with their gifts (literally), spread hope, go on to rule justly, and bring peace and prosperity to the land of Narnia for all. They accomplish this by the will and power of Aslan, of course—but they really do participate!

It’s also worth noting that when Edmund turns his back on his family, he becomes completely ineffectual. He labors in vain through a harsh winter storm, is thrown in jail, tied up, and then literally dragged around by a dwarf until he’s rescued. In his sin, Edmund became powerless to help himself, and powerless to impact the fate of Narnia. Once redeemed he performs one of the greatest acts of valor in Narnian history (breaking Jadis’s wand)!

The Lord created us Imago Dei, and Jesus saves us, to be the Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve we were meant to be.

Now, if you really need to call The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe Narnia’s atonement/redemption story, that’s fine. I get it. But when you do, do not neglect to mention that though Aslan died for Edmond traitor… he rose to enthrone him as King Edmund the Just.

Thanks for reading.

Good stuff!